It’s funny, because I guess everyone has their own idea of what they think a good portrait should be. Ask most parents and to them a good portrait is simply a picture that portrays their child in a flattering way. Ask a model and they’ll say a good portrait is one that makes them look beautiful and sexy. There’s nothing wrong with that. Every parent wants to see their child smile and every model wants to be seen in a flattering light.

What Makes a Good Portrait

Ask most portrait photographers what makes a good portrait and I think the answer you’ll get is entirely different. I think most photographers would define a good portrait as one that reveals something about the subject. But what are most photographers really trying to reveal? From my point of view, when I look at the work of photographers who make this claim, their portraits are not so much about revealing character as they are about forcing the subject to be viewed a certain way. Some photographers try to compel some predefined emotion on the viewer. And that forced emotion is somehow idealized as revealing something important about the subject, as if that forced emotion shows character.

As far as I’ve concerned that’s bull. If everyone looks at a picture and sees the exact same thing and feels the exact same way, what exactly is being revealed? What is really there to see? After all, if everybody sees it how revealing can it be?

With my portraits, the most common criticism I hear is that my pictures are cold and emotionless. And I suppose they are when compared to what most people expect a portrait to be. And that’s fine if that’s what you see. I don’t really expect to please anyone except myself. I’m happy if I do, but I don’t mind the criticism if I don’t. In some ways I even see that criticism as a badge of honor.

But I like to think that if you look at one of my photographs and find it cold and emotionless, either you’re not looking hard enough, or you’re expecting to see something that isn’t there. And I guess that’s sort of the point. I don’t want to tell the viewer what to think or how they should see the subject. When it comes down to it, I could easily manipulate the subject and manufacture any emotion I wanted. But that kind of emotion is easy. It’s sentimental and doesn’t reveal a thing. It’s a campaign slogan or a Victoria’s Secret ad.

Look Deeper

With my portraits I don’t want to tell you what to see. I want you to look, and to look deep, to see what you alone see. Not what I see, or what your wife sees, or even what the subject wants you to see. I want you to see what only you can see, and hopefully that is something that is personal and unique and complex. Just like in real life where the actual person in the picture is seen in a thousand different ways, a portrait should be similarly complex.

I want my portraits to be mysterious and ambiguous. At the same time, I strive to make them rich and complicated, yet deceptively simple as well. I want to strip away the pretense and present a person as they really are. Not how you think they should be, or how I think they should be, or even how they see themselves. I want to present them simply and plainly, open for everybody to see in their own unique way. I don’t think you can do that by forcing your own perception on the viewer.

So when I hear someone say my portraits are cold or emotionless, I say thank you. Then I say look again but try harder this time, and don’t look for what you expect to see but look for what you actually can see. Look at the photograph and view it for what is, not what someone tells you it should be. Look closer and let the subject reveal itself and know that what’s revealed won’t be what’s be on the surface.

To be honest, I have no earthly idea if that is what I achieve with my portraits. That’s better left for others to judge. All I know is that it’s what I try to achieve, and I hope in some small way that I approach that ideal.

Being Drawn Into the Portrait

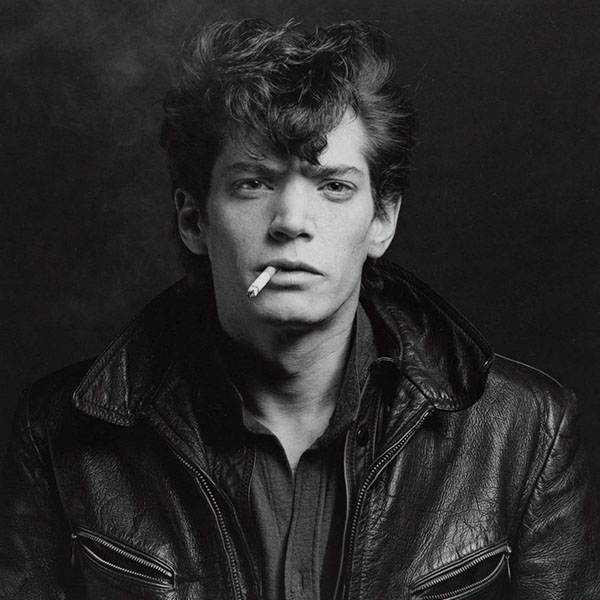

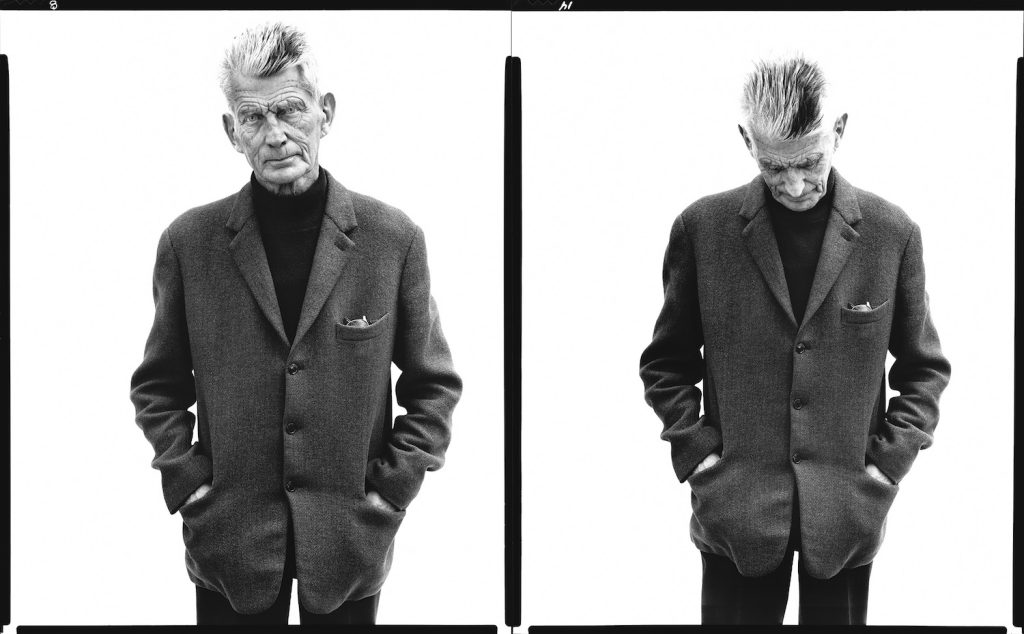

I think that’s why I admire photographers like Robert Mapplethorpe and Richard Avedon and Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, because I think they aspire to that ideal and are largely successful in that pursuit. When I see a Mapplethorpe portrait or a picture from Avedon’s In The American West, I instinctively want to look deeper. I’m drawn into the picture and I think about the person, and I wonder about who they really are and what they really think. I wonder about how they feel and where they came from and where they’re going.

In the end, I think about all of those things and draw my own conclusions. I see the person in the photograph in my own unique way. To me that ambiguity and that mystery is more revealing than a dour grin or sexy pout could ever hope to be. And that is what I think a portrait should aspire to achieve.